After feasting on a large plate of feijoada accompanied by some strategically interspersed cachaça shots, you turn the TV set on and let your body gently slide down the couch, until it finally turns the armrest into a headrest. It is a lazy Saturday afternoon in the mid 80s and the whole family is now being entertained – or, more accurately, being put to sleep – by a screaming, slightly overweight septuagenarian man, dressed as some sort of clown you have difficulty remembering where you have seen before.

By this point, Abelardo Barbosa, aka Chacrinha, aka The Old Warrior, has already concluded his task of revolutionizing Brazilian television broadcasting. Looking rather drained and fed up, he celebrates the end of each of his shows on camera, shouting Thank god it’s over! in relief. His tirades remain outrageous: he awards pineapples as mock trophies to the worst contenders of his talent show and throws huge fillets of codfish into the audience, bursting out in laughter when people start exchanging blows in order to decide who will take the delicacy home.

By giving pineapples as consolation prizes while offering the colonizer’s most recognizable food item as something to be fought over, Chacrinha not only consolidated the pineapple as a national symbol of failure, difficulty and/or shame, but also highlighted his countrymen’s ignorance of the fruit’s status abroad – a somehow ironic inversion, considering the Brazilian tendency of undervaluing all things native and overvaluing European habits, goods and fads; a most probably unintended practical joke with such strong connotations that it kind of fermented well as food for thought, turning out especially juicy in times of decolonial activism.

Perhaps to blame on Main Character Syndrome, turning tables and aiming for the spotlight is an indisputable abacaxi specialty, and in many ways the fruit’s proneness to protagonism, or rather antagonism, is reflected by its recurrent use, in Brazil, as a synonym for trouble, for a difficult or impossible problem to solve, for a point of concern that cannot be overlooked. “Que abacaxi,” someone will giggle whenever they feel pessimistic about your odds of succeeding at any endeavour.

Although pleasing to the eyes and palate, deceitful abacaxis present substantial challenges from the get go. They hardly look inviting in the wild, bearing a sinister resemblance to oversized cross-hatched barbed wires. Pineapple farmers’ attires leave no doubt as to the dangers presented by these crops. And once you pick a ripe one from the ground, considering you avoided grabbing it by the crown, it will probably poke your hand anyway with its crocodilian skin. If you hold it too long, it will tire your arm. Not to mention the herculean effort required to peel it and chop it, which has prompted infinite video tutorials on youtube that work, at best, as a brief distraction to the fact that the task will be, regardless, a time consuming, exhausting and potentially injury-inflicting one.

Fruit shops refrain from commercializing abacaxis (one can only wonder why), leaving it to independent producers who drive hedgehog-looking pineapple trucks around the neighborhoods announcing their presence through extremely poor quality speakers. “Olha o abacaxi,” they scream threateningly, meaning something like “watch out for the pineapple”, as if it is actually coming for you.

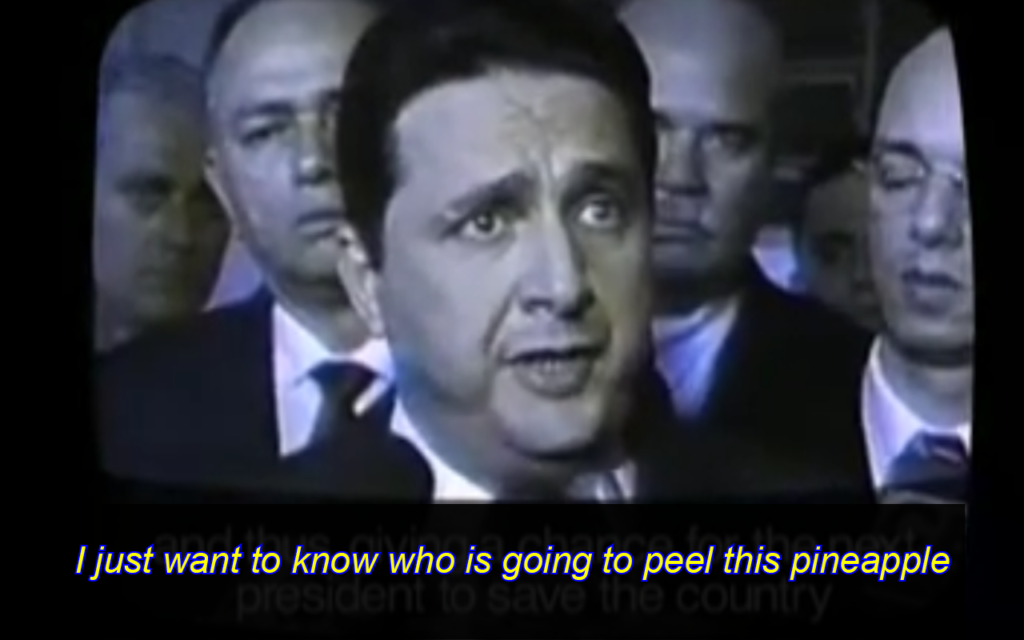

“I just want to know who is going to peel this pineapple,” argued a presidential candidate in 2002, as Brazil faced the choice of either taking a US$ 30 billion loan from the IMF with whooping interest rates or letting its currency plummet in value, rejuvenating a horde of inflation ghosts from the past. Choices must be made, one might say. Abacaxis must be peeled over and over, for such is life: as old problems subside, new, unsuspected ones make their glorious entrance into the stage of worry.

The latest one, of course, is president Jair Bolsonaro himself, an unapologetic right-wing extremist under whose mandate almost 600,000 Brazilians perished due to a carefully devised plan based on negationism and negligence. He has recently been turning his supporters – about 25% of the electorate – against the Supreme Court by asserting that the country is already under a dictatorship implemented by the judiciary. A huge march has been called for September 7, independence day, and Bolsonaro’s supporters are set to storm the streets with signs reading “I authorize it” (meaning a coup d’etat).

In just under three years, the abacaxi of abacaxis has managed to take Brazil back to the levels of poverty and hunger of the late 1990’s. His former environment minister (who is now facing prosecution) was recorded saying that the country should take advantage of the pandemic to “let cattle thrive”, hinting that it would be a great opportunity for turning vast swathes of forests into pastures away from the public eye. For his role in exterminating indigenous populations, Bolsonaro is already being investigated in the Hague, but these processes usually take much longer than the time it takes for unscrupulous politicians to destroy what was accomplished through long years of good policy making and award-winning distributive programs.

As the world watches in slumber from the headrest of their couches, the aluá jar bubbles up furiously in Brazil and no one is letting it burp. Expect shards of glass flying in your direction when the jar explodes. Watch out for the pineapple.