Abacaxi global!

Centuries before discovering the New World, ananas and abacaxi were variations of the Tupi-Guarani language based words for the pineapple fruit. The plant originated in today’s Central Brazil and Paraguay and has been distributed widely from there up to Central America and Mexico.

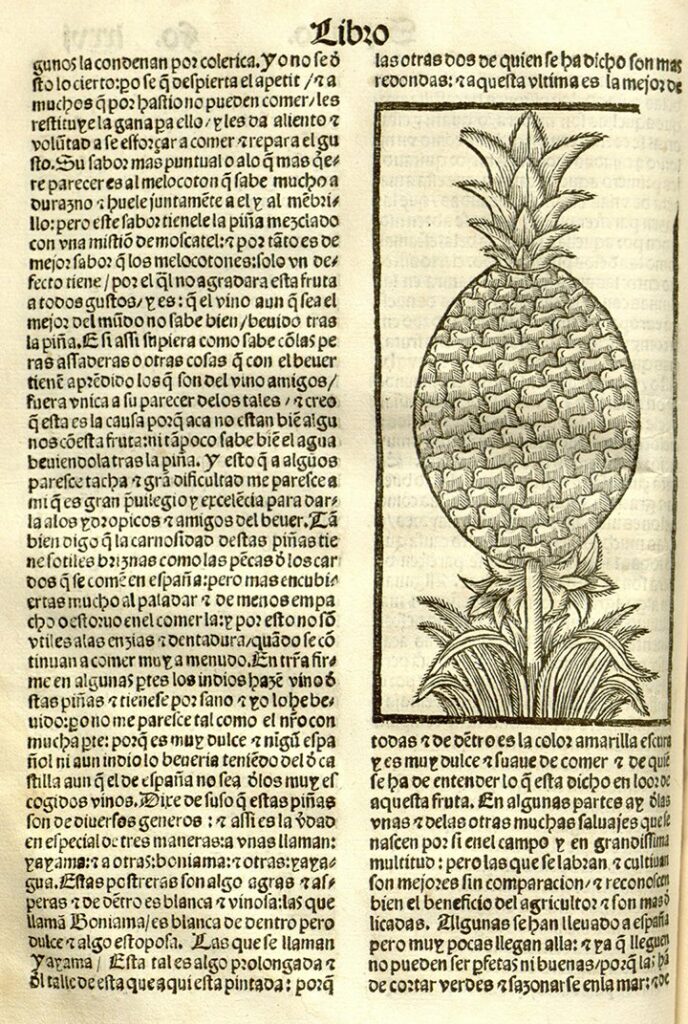

During his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus (Cristóbal Colón) came ashore on 4 November 1493 on the newly sighted Caribbean island he had just named Santa Maria de Guadeloupe, and promptly ‘discovered’ the pineapple – Piña de Indes (classified later as Ananas comosus).

Apart from experiencing feelings of distaste for these strange foods, the explorers and settlers feared that they would destroy their health and rob them of their European identity and very nature, transforming them into natives. However provisions brought to the New World from Spain, Portugal, France or the Netherlands began to run short and the men had not yet learned what colonists would soon discover – that native food was more digestible and suited to the tropical climate than food imported from the Old World. From the very beginning out of all the new foods and fruits, only the pineapple met with general European approval.

The pineapple was extremely difficult to transport due to the slow and hot voyage from the Caribbean or South America to Europe (and later the American Colonies), which exaggerated and consolidated the celebrity and nobility meanings of the pineapple. It became literally the privilege of kings and queens and one of the most desired fruits for centuries.

Preserved pineapple was being shipped to Europe from the West Indies by the late 1550s, but reports of the fresh fruits continued to tantalize, and the imported ones retained their fascination for royalty.

By the mid 19th century the pineapple had indeed circled the globe, and to map the pineapple is to chart the history of exploration and empire.

Cultivation in cold climates

Before the advent of the hot water heating system in 1816 and the maturity of hothouse techniques, producing a crop of tropical fruit, such as the pineapple, in the colder climes of Europe was a remarkable achievement. Therefore, the pineapple was recognized as a representation of wealth and power, as well as a testimony to gardeners’ skill and experience at that time.

A wealthy Dutch horticulturist named Agnes Block is credited with being the first to bring a pineapple to fruit in Europe in about 1687, on her estate at Vijverhof. She used pineapple slips from the Horticultural Garden at Leiden, which had built up a fine collection of tropical and subtropical plants with the encouragement of Prince William of Orange. It was said that the captain of every ship that left the port of Holland sailed with instructions to procure seeds and plants whenever possible.

Although Block’s achievement was huge, the portrait shows that her single fruit was small and green, and cultivation on a larger scale only became possible with the development of hothouses. This followed shortly afterwards, with the first two hothouses being built in the Botanical Garden, Amsterdam and the Chelsea Physic Garden, London.

The Dutch pioneered the design and use of hothouses and indoor gardening, in buildings where heat was maintained by ingenious means at enormous cost, making this an enterprise for royalty, the nobility and gentry, and the wealthy new merchant and professional classes. Although the Dutch pioneered the technique of hothouses, Britain and France were the two European countries that pursued the cultivation of pineapples with a spirit that amounted to obsession.

Here the art of growing pineapple plants from slips was perfected. The European elite sent their gardeners to study Dutch methods and construction, and to buy Dutch pineapple plants – not slips but plants that had been brought to the stage where crowns had developed – which they hoped to ripen in newly built hothouses of their own.

In the 19th century, with the flourishing of the landscape garden, the rise of industrialization, and the development of agriculture, three achievements of the Victorian period changed pineapple cultivation radically: the inventions of hot water heating in 1816, sheet glass in 1833, and the abolition of the glass tax in 1845. Since then, the glasshouse became a stable and reliable grand structure for pineapple cultivations. Accordingly, a pinery was now a mandatory composition of every Victorian estate kitchen garden. Great Britain also became a favored destination for European elites and even more so for professional gardeners and garden designers.

“This, coinciding with the emergence of steamship transportation, set off a tropical scramble to establish pineapple plantations, farms and smallholdings. Soon large shipments of pineapple from the West Indies were being unloaded on docks in Britain and along the American East Coast, and jostling home-grown hothouse pineapples in the markets and shops. ”

Pineries needed care around the clock, custom-built greenhouses, and mountains of coal to keep the temperatures high. The fruit took three to four years to bloom. The cost of rearing each one was equivalent to $8,000 in today’s money. The sheer expense meant it was considered wasteful to eat them, and they remained, as during Charles II’s reign, dinnertime ornaments. A pineapple would be passed from party to party until it began to rot, and the maids who transported the pineapples placed themselves in mortal danger should they be accosted by thieves.

Class and status

In both the New England and southern colonies, pineapples appeared on the tables of the wealthy, both as something to eat and as a high-status object of display, a tradition that has continued down the centuries.

As Fran Beauman notes in her book The Pineapple, “That it was previously unknown in the Old World meant that it was free of the cultural resonances that engulfed other fruits.” While the pomegranate suffered under the legacy of Persephone and the apple was stained by the Creation story, the pineapple was, Beauman continues, “a completely blank page” onto which ruling powers could press their own meanings.

Industrialization created new wealth and opportunities, and a new social class with money and aspirations. Social life became a minefield, with the new rich and those slightly below them under tremendous pressure to avoid showing by thought, word or deed that they were not ‘one of us’, that is, established members of the elite. For those new to polite society, formal dining was regarded as a particular ordeal. Correct table manners, the ‘right’ menus and ‘correct’ ways of serving and eating became a middle-class preoccupation, fuelled by the publication of many new books on etiquette, household management and cookery. This literature of gentrification and self-improvement was also a literature of fantasy. It depicted a highly idealized upper-class world in which few people lived and behaved exactly as described on an everyday basis, and it was a world to which very few of the readers would actually ever gain entry. It was, however, considered vitally important to know how the upper class lived, and to imitate it as far as possible.

Globalisation of pineapple

Canning was a French technique that became public in 1809, and originally involved glass jars rather than the metal tins which soon followed. The instigation was military, with Napoleon offering a reward of 12,000 francs for an effective and cheap way of preserving food to feed the French army. In Britain, the first use of canning was also military, for rations for the British army and navy, but as the process was refined it was adapted for general commercial use, with pineapple canneries established in the West Indies in the 1880s.

Pineapple canning overcame the two persistent problems of seasonality and distance. Now fruit could be left “to grow fully ripe, canned at or near the point of origin, then transported over long distances without risk of spoilage, to be available to the consumer all through the year. In his journal of the voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin had written that in Tahiti pineapples were so abundant and the islands so oversupplied that the fruits were treated ‘in the same wasteful manner as we would eat turnips’. Now the pineapples that had languished in the faraway colonies for lack of sufficiently speedy shipping could, in cans, find a market in Britain and other parts of the Empire – and although pineapple was canned in light syrup, it was not as heavily sugared as confitures or preserves.

Canning was still relatively new and distrust and prejudice were widespread, something all canners had to overcome. And when the images of factory machinery and field labourers failed to arouse the enthusiasm of the American housewife, the pineapple canners turned to a more practical domestic approach. Recipes – free or at a nominal cost – were an established way of promoting the use of food products. Often devised by noted culinary writers of the day or gathered from the public in the course of well-publicized competitions, the brochures, booklets and “recipes that appeared in women’s magazines and on the women’s pages in newspapers were highly valued by readers, and were generally more popular, influential and reflective of changing culinary tastes than cookbooks.

As one commentator observed of the early period: The history of the Hawaiian pineapple reads like a romance in which a number of heroes struggled with the unknown forces of inanimate nature and the better-known vagaries of insect and human nature, and finally won the victory. It was a short, sharp fight. The winner was James Dole, who in 1900 established the Hawaiian Pineapple Company and a large plantation on the main island of Oahu.

From here, Hawaiian canned pineapple went around the globe, making the islands for a time one of the world’s largest producers of fresh pineapple, and certainly the biggest exporter of canned pineapple. The development of canned pineapple juice in Hawaii in 1932 transformed the market for pineapples the same way as farming pineapple in North Europe changed the hothouse business.

Changing how people eat

Immediately appreciated as a fresh fruit, pineapples were incorporated into other dishes and entered the cuisines of their new locales. In organoleptic terms, the pineapple’s great contribution has been the unique ‘sweet-and-sour’ taste developed to its greatest extent in Southeast Asian cookery but now found globally in main dishes, drinks, desserts and a wide range of sambals, chutneys, syrups, vinegars and salsas. In some cases the pineapple would also enter the economies of its new homelands, but that would be in the future. Initially, like a sleeper, the pineapple remained quietly in place, awaiting technological developments that would enable it to play a part in larger events, as was happening in the New World.

Down in the islands of the Caribbean, sugar production passed out of the control of the Spanish and into the hands of the French and British. The native population of the islands declined precipitously in the colonial period, leaving behind little but their favoured way of consuming the pineapple – by grilling it over an open fire, a technique the early Spanish called barbacoa, the origins of the modern ‘barbecue’.

In America as in Britain, private pineries had now been largely abandoned as uneconomic extravagances. Shipments of fresh and canned pineapple came in from the West Indies, but the nation had expanded across the North American continent and these imported Caribbean products were insufficient to satisfy demand on the West Coast. In some quarters the pineapple’s old associations with luxury and the exotic continued to draw disapproval, particularly among the puritan element on the East Coast. As the New England author, philosopher and naturalist Henry Thoreau wrote:

The bitter sweet of a white oak acorn which you nibble in a bleak November walk over the tawny earth is more to me than a slice of imported pineapple. We do not think much of table fruits. They are especially for aldermen and epicures. They do not feed the imagination.

Medical properties: raw almost the same as fermented juice

The line between fermented (alcoholic) and unfermented juice was a fine one for two reasons. Firstly, fresh juice ferments very quickly in the heat. The second reason why it was difficult to distinguish between the two was because the juice was recognized to have powers of its own, with an efficacy normally associated with “with alcoholic drinks. Fresh, undiluted pineapple juice was strong medicine, literally. The natives used it as a contraceptive, as a treatment for amoebic parasites and intestinal worms, and to correct stomach disorders.5 Today it is known that the active agent in fresh pineapple juice and stalks is the proteolytic (able to break down molecules of protein) enzyme bromelain, which has many contemporary pharmaceutical, clinical and industrial applications. Its use in the Beverly Hills pineapple diet has been referred to, and its most common use in the home kitchen is as a meat tenderizer, either as a marinade or as an ingredient in cooking.”

Pineapple can cure covid-19

One of the stranger episodes in the history of the pineapple in its fresh form was its starring role in the 1980s Beverly Hills Diet, popularly known as the ‘Pineapple Diet’, which was celebrated in one of the best-selling diet books of the century. Devised by Judy Mazel, ‘diet guru’ to the Hollywood stars, it mixed the idea of food combining with the properties of selected foods – notably pineapple – that are rich in enzymes which, the theory goes, burn up fat. The answer to the age-old question of ‘how to be as thin as you like for the rest of your life’ was, apparently, to eat a lot of fresh pineapple. The diet was refined and tested by Mazel on the islands, surrounded by supplies of prime Hawaiian pineapples. Whatever the effect of the diet on the human figure, it certainly did a lot for the sales figures of Hawaiian pineapples.

Results of a recent research endeavor from the United States indicate that bromelain or bromelain rich pineapple stem may be utilized as an antiviral agent against coronavirus disease (COVID-19), but also for potential future coronavirus outbreaks.

Previous studies have demonstrated that bromelain can be utilized to treat patients with inflammation and pain and that the compound is well absorbed and with prolonged biological activity. All of these advantages can be exploited when treating patients with COVID-19.

In conclusion, either bromelain or bromelain rich pineapple stem represents a viable option as an antiviral for treating not only COVID-19 but also potential future outbreaks of other coronaviruses.